No Backbone Equals No Rights?

October 31, 2025 2025-11-02 8:30No Backbone Equals No Rights?

By: Srishti Sawant

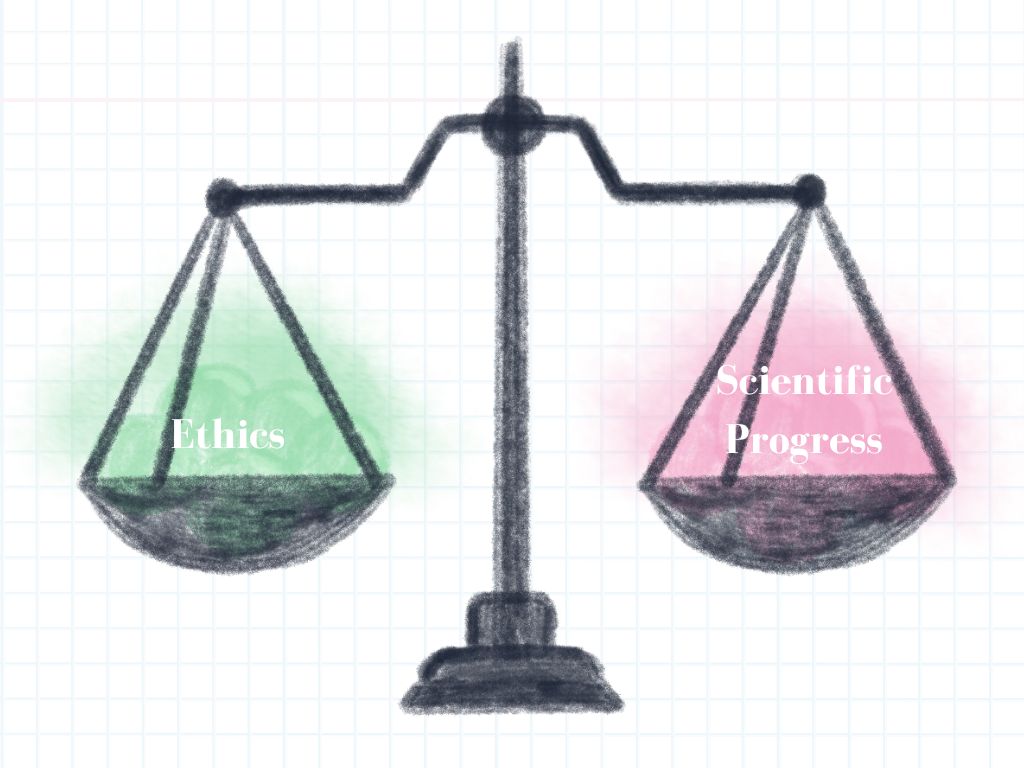

When it comes to scientific research, ethics and experimentation share a thin line. In the world of research, that line blurs even further when the subject studied is living.

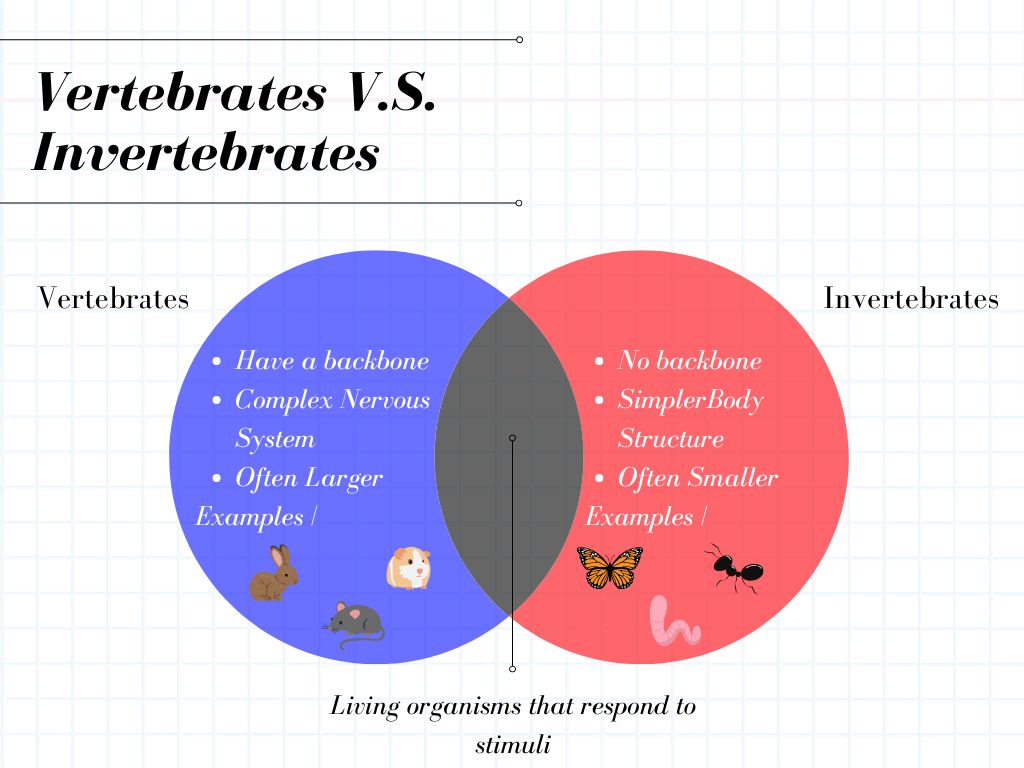

At Innovation Academy, many student researchers conduct projects involving living organisms, either as part of their Pinnacle Project, Science Fair, or other research experiences. However, due to Institutional Review Board (IRB) guidelines, students are only allowed to test on invertebrates—organisms without a backbone—fruit flies, E. coli, or small worms, unless granted special permissions through an arduous approval process. These rules are designed to protect vertebrates, which are believed to experience more complex pain responses because they possess a nervous system.

But the question remains: does the lack of a backbone mean a lack of rights?

According to a 2022 Nature article, “Ethical and regulatory oversight of research animals is focused on vertebrates and rarely includes invertebrates” (Brunt et al., 2022).

While invertebrates make up the vast majority of the animal kingdom, they are often excluded from ethical review because they are assumed to lack the capacity to suffer. However, this assumption has become an ongoing debate in the scientific community. Some researchers argue that testing on invertebrates is justified since these organisms lack complex nervous systems and pain receptors that vertebrates such as ourselves possess. Others, however, rebut that the absence of clear evidence of suffering does not mean the absence of suffering itself. Emerging studies on cephalopods and insects, for instance, have shown behaviors suggesting possible forms of discomfort or learning. Such discoveries have prompted questions about where the moral boundary should be drawn between scientific progress and ethical responsibility; just because we can doesn’t always mean we should.

Mr. Robinson, a research teacher at IA, offers a thoughtful perspective when guiding students through the decision of whether or not to test on a living organism (vertebrate or invertebrate). “Your personal ethics should always be placed above the scientific ones,” he said. While the guidelines exist to protect animals and ensure research safety, Mr. Robinson believes students must also consider their own moral boundaries. “Although science says that an organism without a backbone has no feelings, therefore it is okay to test on,” he added, “you decide to believe whether it is okay for you to go ahead with such a test or not.”

For some student researchers, that decision can be simple, while for others, not so much. Student researcher Mary Tseretian [11] reflected on her project, saying

“Honestly, I didn’t think too much about my choice. I just chose to go ahead with my research that tests on Drosophila and E. coli [two invertebrate species].”

Like many other IA students, Mary’s project followed all IRB guidelines and focused on invertebrates. However, her comment brings to light how easily ethical questions can be overlooked in the rush of scientific curiosity.

The IRB, which reviews all research proposals before approval, notes that ethical standards are not just “checklist items” but part of developing good scientific habits. Still, some students and teachers question whether limiting research to invertebrates creates biased data. After all, invertebrates make up over 95% of all animal species, yet their biology differs drastically from vertebrates.

This difference raises a larger concern and an area of justification for researchers testing on living organisms. Since invertebrates lack a nervous system, they are often treated as fair game for experimentation. It’s perfectly logical on paper. If they can’t feel pain, then no harm is being done. However, this mindset risks reducing living organisms to tools, ignoring the moral responsibility that comes with experimentation.

For others, however, these restrictions are not limitations but lessons in creativity. Students have found innovative ways to explore behavior, environmental changes, and chemical effects using fruit flies or E. coli. Some even argue that studying simpler organisms first helps refine experimental design before moving on to more complex systems later in college or professional labs.

In the end, whether an organism has a backbone or not, the responsibility to test on it rests with the researcher. As Mr. Robinson put it, it comes down to personal ethics.

References

Brunt, M. W., Kreiberg, H., & Von Keyserlingk, M. a. G. (2022). Invertebrate research without ethical or regulatory oversight reduces public confidence and trust. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 9(1). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-022-01272-8

situs toto bento4d